This month's focus is on Lyme disease, or better yet the bacteria that causes Lyme disease, typically carried by ticks. It is very likely that living in California Lyme disease and how you can contract it may not be on your safety radar as California is not considered a top area for spreading the bacteria and contracting Lyme disease, however, recent maps of reported cases shows a growing number of cases being reported in the Pacific Northwest and Northern California. As the number of reported cases continue to grow it is important to know how to protect yourself and prevent the spread of Borrelia burgdorferi especially if you participate in sports and activities that could expose you to an increased risk or you travel to regions with a higher risk of infected ticks.

The sources for for this month's blog will be listed at the end of the article, but the primary source of information is the CDC website specific to Lyme disease, including all images.

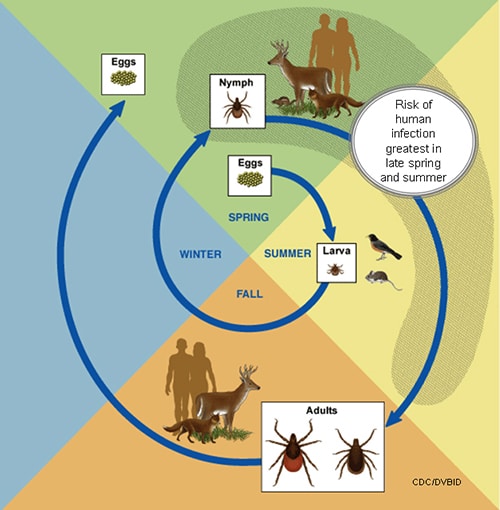

THE BACTERIUM: According to the CDC, the Lyme disease bacterium, Borrelia burgdorferi, and is found in the blacklegged tick (deer tick, lxodes scapularis) in the northeastern, mid-Atlantic, and north-central US and the western blacklegged tick (lxodes pacificus) on the Pacific Coast. B. burgdorferi life cycle typically last two years. There are four stages: egg, six-legged larva, eight-legged nymph and adult. Blacklegged ticks can feed on blood from mammals, birds, reptiles and amphibians and require a new host at each stage of life.

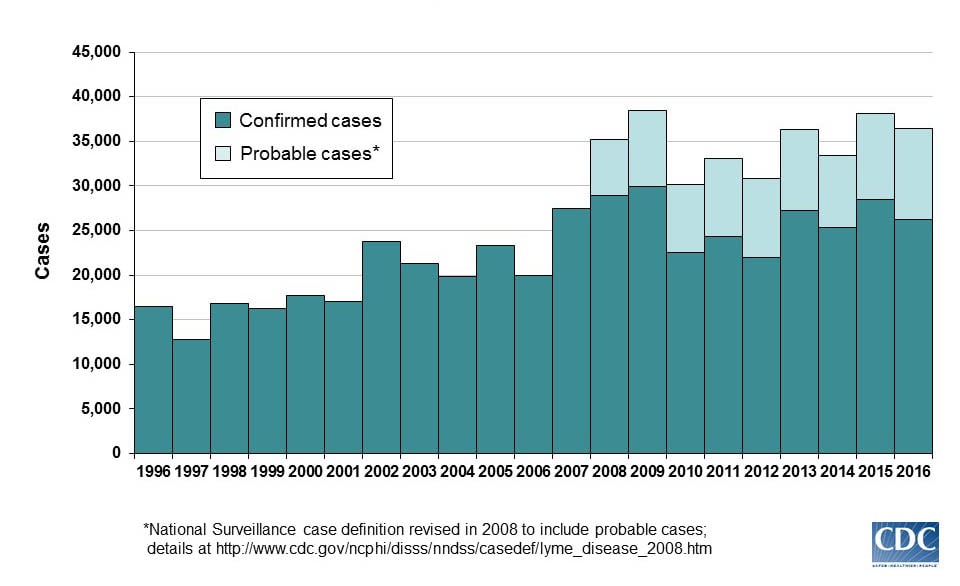

While Lyme Disease causing bacteria has been more prevalent in the northeast and mid-Atlantic over the last 15 years is has become more prevalent in the upper Midwest and increasing cases in Washington, Oregon and Northern California. As of 2015, 95% of confirmed Lyme disease cases were reported in 14 states: Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Vermont, Virginia and Wisconsin. It is also the most commonly reported vector borne illness and is prevalent in wooded areas where they can wait for potential hosts to pass by on the tips of grasses, shrubs and other plants and vegetation.

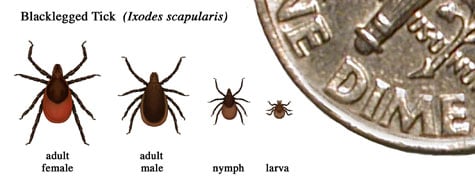

MODE OF TRANSMISSION: The B. burgdorferi is spread through the bite of the infected blacklegged tick. Ticks can attach to any part of the body, but typically are found in hard-to-see areas such as the groin, armpits and scalp. Generally, the tick must stay attached for 36 to 48 hours to transmit B. burgdorferi. Humans are most often bitten by immature ticks in the nymph stage. These nymphs are very hard to see, less than 2mm in width – think poppy seed. The nymphs are most active during the spring and summer months (May – July). Adult infected ticks can also spread Lyme disease, but most are more active during the cooler months of the fall. Additionally, they are usually much bigger and easier to find and remove before transmitting the bacteria.

Ticks will attach to their host by grasping the skin and cutting into the surface. As this occurs ticks secrete a small amount of saliva that have anesthetic properties so the person (or animal) cannot feel the tick attaching itself. A blacklegged tick will attach itself and suck blood slowly for days and then drop off when finished feeding. If the tick is not infected, but the host caries any bacteria, such as B. burgdorferi, the tick will ingest the pathogen and spread it to its next host. If the tick is already infected with the bacteria it can transmit the bacteria to its host, animal or human.

SIGNS & SYMPTOMS:

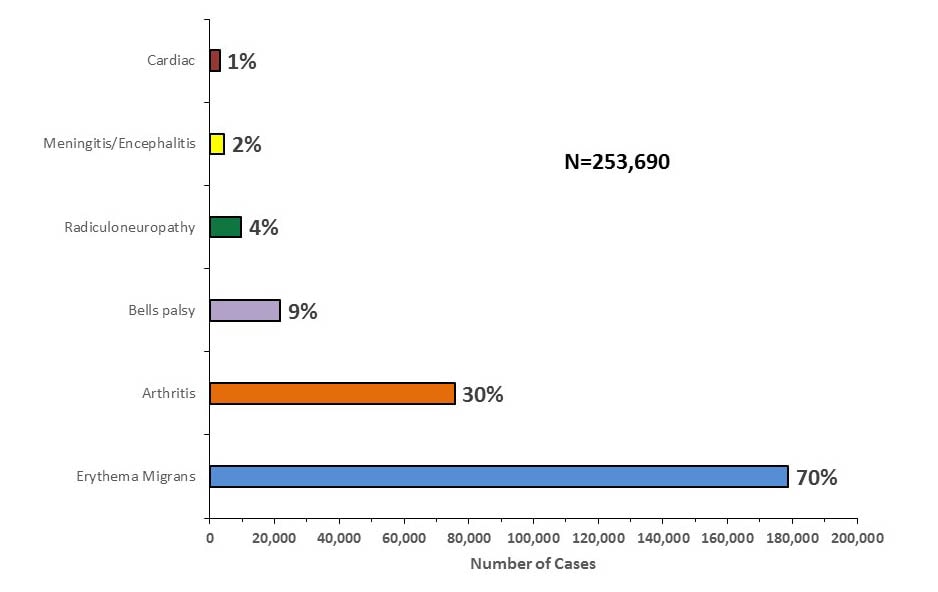

Early signs and symptoms (3 – 30 days) include: fever, chills, headache, fatigue, muscle and joint aches, swollen lymph nodes and erythema migrans (EM) rash (bulls eye rash). EM occurs in approximately 70 to 80% of infected persons, begins an average of seven days after the bite. EM may feel warm, but is rarely itchy and can expand is size over a period of days.

Later signs and symptoms include: severe headache and neck stiffness, additional EM rashes on other areas of the body, arthritis with severe joint pain and swelling, facial palsy, dizziness, shortness of breath and in rare cases heart palpitations or irregular heartbeat.

TESTING/DIAGNOSIS:

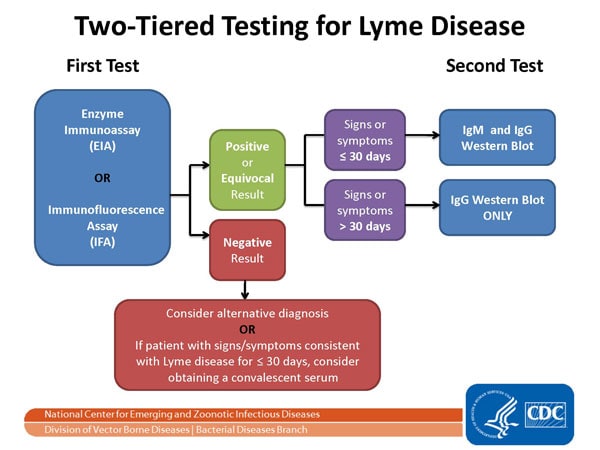

Nearly 300,000 cases of Lyme disease are diagnosed annually in the US. A two-step blood test is recommended as best practice by the CDC. Both parts of the test can be completed using one blood sample and looks for evidence of antibodies against B. bu. It is important to complete step one, the EIA or enzyme immunoassay and then the immunoblot or “Western blot” test. Best practice is not to skip part one and go directly to part two. The two tests are designed to work together and failing to perform the test properly can lead to in increased risk of false positive and misdiagnosis and improper treatment.

TREATMENT & MANAGEMENT: When identified early a proper course of antibiotics usually results in a rapid and complete recovery. The most common antibiotics prescribed include doxycycline, amoxicillin, or cefuroxime axetil. Intravenous antibiotics may be needed for those with certain neurological or cardiac forms of Lyme disease.

To learn more about Post-treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome (PTLDS) refer here. According to much research including, Time for a Different Approach to Lyme Disease and Long-Term Symptoms (2016) in the New England Journal of Medicine there is some controversy on how PTLDS should be treated. Approximately 10 to 20% of those are treated for Lyme disease have lingering symptoms. There is an ongoing debate about how to best manage these patients. According to a recent editorial, while a longer course of antibiotics has been recommended to these patients by the CDC, not all healthcare providers feel the evidence does not support this approach according to a 2016 NEJM editorial.

PREVENTION: Prevention can be done in three simple steps:

1) avoid direct contact with ticks;

2) repel ticks on skin and clothing; and

3) Find and remove ticks from your body.

It’s important when in a wooded area to stay in the center of trails and avoid areas with high grasses and leaf litter. Using a repellent that contains 20% or more DEET, picaridin or IR3535 on exposed skin can protect you for several hours. Treat your clothing and gear with this repellent as well following the recommended amounts. One resource to help is available by visiting the EPA online tool.

LYME DISEASE IN ATHLETES: Athletes most at risk for Lyme disease are those who participate in outdoor sports during high risk seasons – runners, mountain bikers, hikers. While Southern California doesn’t present a major risk based on where most cases are reported athletes should still be diligent when participating in activities outside in wooded areas and protect yourself and perform a tick check. When traveling to other parts of the country, you should also recognize your risk.

There are no specific return-to-play guidelines for athletes as it relates specifically to Lyme disease. Treatment remains prompt recognition and diagnosis followed by a proper course of antibiotics. There is a potential challenge in diagnosing athletes, if the EM (bulls eye rash) is missed, since athletes often complain of fatigue and muscle pain due to their sports participation the disease could go undetected and diagnosed. It seems reasonable to allow those who respond to treatment to return to play after a graduated exercise program under the direction of a physician, but in cases where symptoms persist following treatment exercise recommendations and allowances are unclear.

DISCLAIMER:The content contained in this blog is for informational purposes only. The content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician, athletic trainer, or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. If you think you may have a medical emergency, call your doctor or 911 immediately.

RESOURCES:

CDC: Lyme Disease. https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/ Accessed May 2018.

Paul M Lantos. Chronic Lyme Disease: The Controversies and the Science. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2011;9(7):787-797.

Kevin M. DuPrey, DO. Lyme Disease in Athletes. Cur Sports Med Reports. 2015; 14(1):51-55.

Michael T. Melia, MD, and Paul G. Auwaerter, MD. Time for a Different Approach to Lyme Disease and Long-Term Symptoms. N Engl J Med 2016; 374:1277-1278.